Researching a past change of name

Contents

- Finding proof of a change of name

- What is a deed poll?

- How can I find out if a deed poll was enrolled?

- Change of name declarations 1939–1945

- Changes of name by foreigners in the UK 1916–1971

- Changes on a birth certificate

- Royal licences

- Private Acts of Parliament

- Phillimore and Fry Index to Changes of Name 1760–1901

Finding proof of a change of name

It’s always been possible in Great Britain, and Ireland, to change your name without having to register the change with any official body. Anyone can start using a new name at any time, as long as it’s not for a fraudulent or illegal reason.

For this reason, people looking for a formal record of a change of name will often find that it simply doesn’t exist. Historically, many people preferred not to draw attention to their change of name. For example, when divorce was more difficult, some people simply took their new partner’s name to allow them to appear married, and to make any children appear legitimate.

What you’re more likely to find, is a trail of records in one name, and — after a certain point in time — another trail of records in another name. The challenge is to find evidence that the two trails belong to the same person. There may not be any single document that links the two names, which can be very frustrating for researchers.

Where people did wish to make their change of name more official, they might have —

- made announcements in the press (you can search the Times online archive (subscription needed) or the British Newspaper Archive (subscription needed) , or consult the British Library’s collection (on 48 hours’ notice) at either Boston Spa or the Newsroom at the British Library in St Pancras )

- made a statutory declaration before a Justice of the Peace or Commissioner for Oaths

- changed their name by deed poll.

What is a deed poll?

A deed poll is a kind of contract where you formally commit yourself to changing your name to something else. Usually, a solicitor or legal firm (such as Deed Poll Office) will draw up the deed poll, and the person changing their name will sign the document. The legal firm may keep a copy on file (Deed Poll Office doesn’t actually do this) — but it may or may not be a certified copy, and the file is unlikely to be kept for more than five years.

People born in England & Wales may ask for their deed poll to be enrolled, for safekeeping, in the Enrolment Books of the Senior Courts of England & Wales (formerly the Close Rolls of Chancery), at the Royal Courts of Justice in London. However, this isn’t free, and most people decide against it considering the complexity and expense of it. Thus many people who seek a record of an enrolled change of name are disappointed.

How can I find out if a deed poll was enrolled?

Deed polls 1914 to present (online)

Search the London Gazette by name for the person you’re researching. From 1914 all enrolled deed polls had to be advertised in the Gazette.

Deed polls 1851–February 2021

Visit the National Archives in Kew and consult the indexes to enrolled deed polls.

The indexes cannot be searched online.

For 1851 to 1903 first consult the indexes in C 275 — they show only the former name. This will enable you to access the relevant document in C 54 . Indexes and the enrolment books for 1903 to 2021 are in J 18 . The indexes show both the former and the new name, either as a note or a cross-reference.

Indexes from 1945 to 2021 can be consulted freely, but you’ll need to register as a reader if you want to —

- consult indexes from before 1945

- view the original deed poll and/or purchase a certified copy

If you cannot visit in person, you can pay for someone to do research for you .

Deed polls February 2021 to present

Contact the King’s Bench division of the Royal Courts of Justice, at kbdeedspoll@justice.gov.uk or by calling 020 3936 8957 (option 6, open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday), for details of enrolments since the end of February 2021.

Change of name declarations 1939–1945

During the Second World War, people wanting to change their name had to make a declaration to that effect and publish details in the London, Edinburgh or Belfast Gazette, 21 days beforehand. This was to allow the National Registration records to be altered and an identity card and ration book to be issued in the new name.

The original declarations were destroyed when National Registration was abolished in 1952 but you can search the London, Edinburgh or Belfast Gazettes for the published details.

Changes of name by foreigners in the UK 1916–1971

In 1916, enemy aliens resident in Britain were forbidden to change their names. In 1919 the ban was extended to all foreigners in Britain and was only removed in 1971.

Exceptions to this rule were —

- if a new name was assumed by royal licence

- if special permission was given by the Home Secretary

- if a woman took her husband’s name on marriage

It may be useful to search the London Gazette , as it was often used to advertise changes of name in the first two instances.

Changes on a birth certificate

It’s possible under certain circumstances to record a new name on a birth certificate.

This may have happened if —

- a mistake (of fact) was corrected

- the father’s name was added to the birth certificate

- the parents got married

- a new name was recorded on the birth certificate

A birth certificate is never amended — it’s an important historical document, and this would be illegal. Any change made by the Registrar would be made by —

- annotating the birth register entry, either in the margin or at the foot of the document (typically to correct a mistake of fact)

- making a new register entry, replacing the old one

When a certificate is changed, all new certificates will show the annotations, or will be issued from the new entry (depending on how the change was made).

Royal licences

Royal licences to a change of name were common in the 18th and 19th centuries, but in later years would be issued where —

- an inheritance depended on someone taking the deceased’s name

- marriage settlement required a husband to adopt his wife’s name

- a change of name also required a change to a coat of arms

Information relating to Royal licences can be found in —

- The National Archives

- The London Gazette

- The Royal College of Arms

The National Archives holds a small number of warrants for Royal licences to changes of name in the following series of records (please note they’re not searchable online):

- Secretaries of State: State Papers: Entry Books (SP 44) for the period up to 1782

- Home Office: Warrant Books, General Series (HO 38) from 1782 to February 1868

- Home Office: Change of Name and Arms Warrant Books (HO 142) from February 1868 onwards

There’s also some correspondence describing individual examples of changes of name in —

- Home Office: Registered Papers (HO 45) for the period 1841–1871

- Home Office: Registered Papers, Supplementary (HO 144) for the period 1868–1959

You can search the London Gazette by name for any references to changes of name.

The Royal College of Arms has records relating to Royal licences. From 1783, applications for a Royal licence were either made through, or required a report from the college. Use their enquiry form to request more information.

Private Acts of Parliament

Some changes of name were made by a private Act of Parliament — usually for the same reasons as those made by Royal licence (see above). This was fairly common in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but since 1907 has only been used once.

Acts of Parliament are published in printed volumes arranged by year. The National Archives library has a set as do some other libraries. It may be helpful to —

- search through the list of Private Acts of Parliament which changed a person’s name (from 1539 to date)

- confirm if an Act was passed and in which year

- consult the appropriate volume of the printed series of Acts

The best place to look at the Original Acts is the Parliamentary Archives in London.

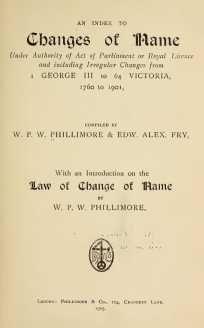

Phillimore and Fry Index to Changes of Name 1760–1901

The Index to Changes of Name 1760–1901 compiled by W.P.W. Phillimore and Edward Alex Fry is made up of information from the following sources:

- Private Acts of Parliament

- Royal Licences published in the London and Dublin Gazettes

- notices of changes of name published in The Times after 1861 with a few notices from other newspapers

- registers of the Lord Lyon (King of Arms) where Scottish changes of name were commonly recorded

- records in the office of the Ulster King at Arms

- some private information

It doesn’t include —

- changes by Royal licence not advertised in the London Gazette

- changes by deed poll that were enrolled but not advertised in The Times

To read the book you can —

- view the book online (or save it to your computer)

- view a copy at the National Archives

- search for a copy in a library near you (the ISBN is 1861500432)

This page contains some public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0